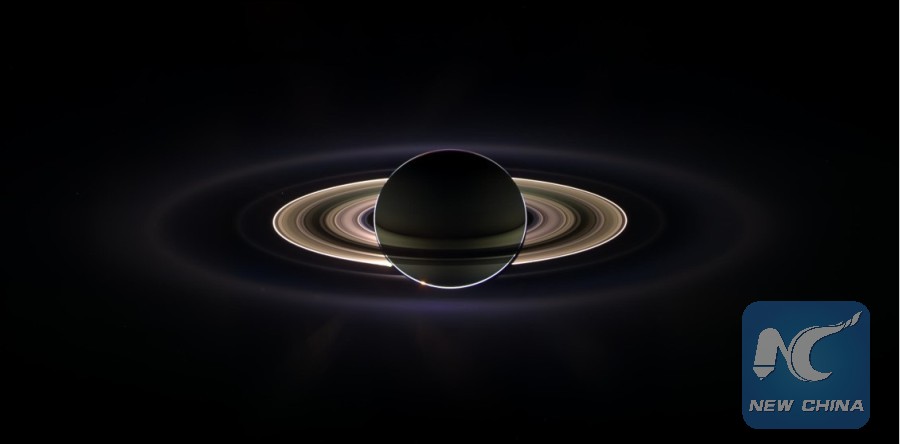

With giant Saturn hanging in the blackness and sheltering Cassini from the sun's blinding glare, the spacecraft viewed the rings as never before, revealing previously unknown faint rings and even glimpsing its home world. This marvelous panoramic view was created by combining a total of 165 images taken by the Cassini wide-angle camera over nearly three hours on Sept. 15, 2006. (Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute)

LOS ANGELES, Sept. 16 (Xinhua) -- After 20 years in space, the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)'s Cassini spacecraft was running out of fuel.

To protect moons of Saturn that could have conditions suitable for life, the long-lived traveler from Earth made a fateful plunge into the atmosphere of Saturn Friday morning, ending its 13-year tour of the ringed planet.

It's hard to say goodbye, not only for the entire Cassini team, but everyone who looks up at Saturn in the night sky. So, why Cassini matters?

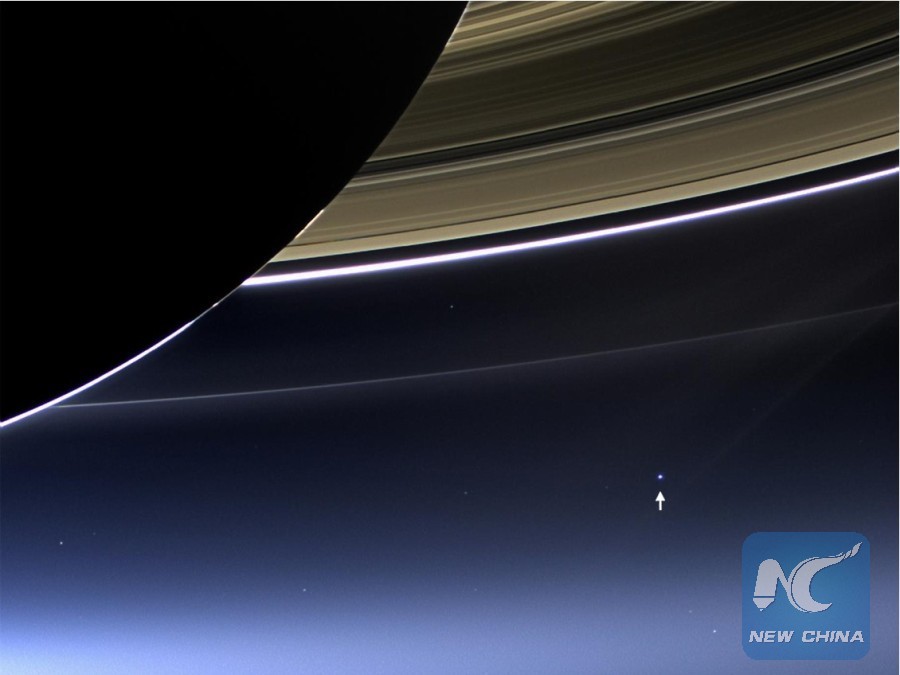

In this rare image taken on July 19, 2013, the wide-angle camera on NASA's Cassini spacecraft has captured Saturn's rings and our planet Earth and its moon in the same frame. Earth, which is 898 million miles (1.44 billion km) away in this image, appears as a blue dot at center right; the moon can be seen as a fainter protrusion off its right side. An arrow indicates their location in the annotated version. This is only the third time ever that Earth has been imaged from the outer solar system. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

VASTLY EXPANDED OUR KNOWLEDGE

Launched in 1997, the 3.26-billion-U.S.-dollar Cassini-Huygens mission has been touring the Saturn system since arriving at the sixth planet from our sun in 2004. The Huygens lander separated from Cassini and plopped down on the surface of Saturn's moon Titan shortly after the arrival.

The Cassini probe had been planned to study the Saturn system until 2008, but the mission was given two extensions that stretched its lifetime into 2017.

During its journey, Cassini has made numerous dramatic discoveries. From Cassini, our knowledge of gas giants, ring systems and icy moons has vastly expanded.

Most excitingly, in revealing that Saturn's moon Enceladus has many of the ingredients needed for life, the mission has inspired a pivot to the exploration of "ocean worlds" that has been sweeping planetary science over the past decade, experts say.

According to NASA, the more recent revelation that a much smaller moon like Enceladus could also have not only liquid water, but also chemical energy that could potentially power biology, was staggering.

Cassini also performed 127 close flybys of Saturn's haze-enshrouded moon Titan, another of Saturn's moons with some of the most Earth-like features discovered in our solar system that may now be a candidate for future exploration.

By pulling back the veil on Titan, Cassini has ushered in a new era of extraterrestrial oceanography.

The information Cassini gathered has enabled scientists to make discoveries that have warranted the publication of nearly 4,000 scientific papers, according media reports.

"Cassini has transformed our thinking in so many ways, but especially with regard to surprising places in the solar system where life could potentially gain a foothold," said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate at Headquarters in Washington. "Congratulations to the entire Cassini team!"

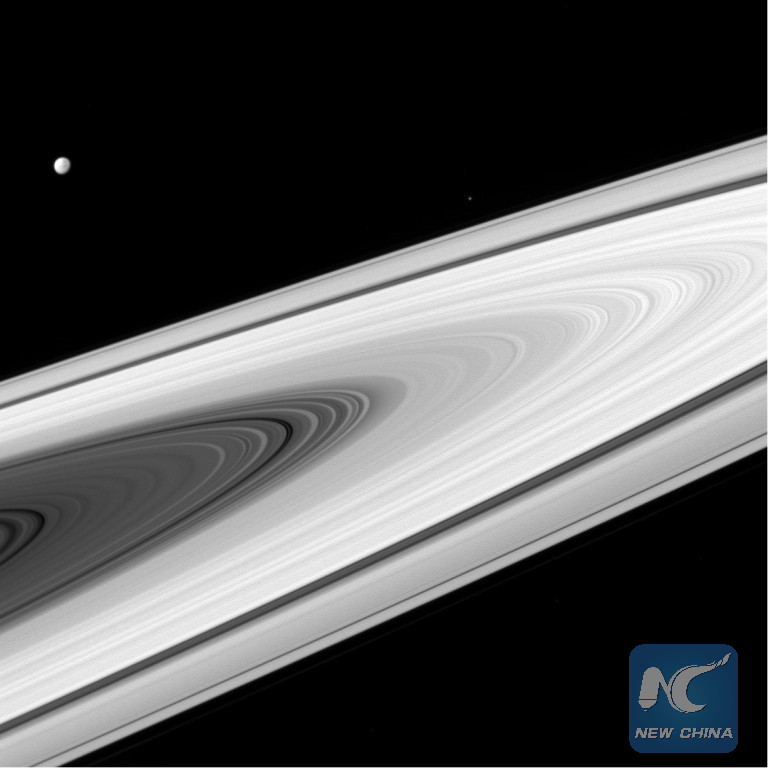

This view shows Saturn's northern hemisphere in 2016, as that part of the planet nears its northern hemisphere summer solstice in May 2017. Cassini scanned across the planet and its rings on April 25, 2016, capturing three sets of red, green and blue images to cover this entire scene showing the planet and the main rings. The images were obtained using Cassini's wide-angle camera at a distance of approximately 1.9 million miles (3 million km) from Saturn and at an elevation of about 30 degrees above the ring plane. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

REMARKABLE STORY OF EXPLORATION

Cassini's plunge brings to a close a series of 22 weekly "Grand Finale" dives between Saturn and its rings, a feat never attempted before by any spacecraft.

No other mission has ever explored this unique region. What scientists learn from these final orbits will help to improve our understanding of how giant planets, and planetary systems everywhere, form and evolve.

"It was exactly those data that led me into science, growing from a young student to an established researcher," planetary scientist Cui Jun, who started to work on the Cassini data as early as 2006, told Xinhua.

Between April and September 2017, Cassini has undertaken a daring set of orbits that is, in many ways, like a whole new mission.

On its final orbit, the probe has even made groundbreaking scientific observations of Saturn. Before contact was lost, eight of Cassini's 12 scientific instruments were operating.

In particular, the spacecraft's Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) was directly sampling the atmosphere's composition, which cannot be done from orbit.

As planned, data from eight of Cassini's science instruments were beamed back to Earth, according to NASA. Mission scientists will examine the spacecraft's final observations in the coming weeks for new insights about Saturn, including hints about the planet's formation and evolution, and processes occurring in its atmosphere.

As predicted, traveling at approximately 120,000 km per hour, Cassini began its entry into Saturn's atmosphere at an altitude of about 1,915 km above the planet's estimated cloud tops at 3:31 a.m. PDT (1031 GMT) on Friday, with a confirming signal received on Earth at 4:55 a.m. PDT (7:55 a.m. EDT).

During its final journey, Cassini was sending back new and unique science to the very end. Due to the travel time for radio signals from Saturn, which changes as both Earth and the ringed planet travel around the Sun, events have taken place there 83 minutes before they are observed on Earth.

The spacecraft's final signal was like an echo. It has radiated across our solar system for nearly an hour and a half after Cassini itself has gone.

"Cassini was the most significant outer solar system space mission since the Voyager spacecraft of the 1980s. It will be at least a decade until we have another similar spacecraft, if serious work is started now," planetary scientist Seth Jacobson said in a statement.

This image looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 3 degrees above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft wide-angle camera on April 2, 2016. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

POWERFUL INFLUENCE ON FUTURE EXPLORATION

"For me, September 15 is not the end of the mission. My students and myself have at least five papers done with the Cassini data, to be submitted later this year. I believe this will continue for the following decades because the Cassini-based science will never die," Cui told Xinhua.

As the Cassini spacecraft ends its long journey rich with scientific and technical accomplishments, it is already having a powerful influence on future exploration.

Results from Cassini poured in for over a dozen years during the life of the mission and will continue for decades.

Many lessons learned during Cassini's mission are being applied to planning NASA's Europa Clipper mission, planned for launch in the 2020s, according to the U.S. space agency.

In a recently completed study, a variety of potential mission concepts are discussed, delivered to NASA in preparation for the next Decadal Survey, including orbiters, flybys and probes that would dive into Uranus' atmosphere to study its composition.

Future missions to the ice giants might explore those worlds using an approach similar to Cassini's mission.

"It's a bittersweet, but fond, farewell to a mission that leaves behind an incredible wealth of discoveries that have changed our view of Saturn and our solar system, and will continue to shape future missions and research," Michael Watkins, director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), said in a statement.

In the decades following Cassini, scientists hope to return to the Saturn system to follow up on the mission's many discoveries. Mission concepts under consideration include spacecraft to drift on the methane seas of Titan and fly through the Enceladus plume to collect and analyze samples for signs of biology.

"Cassini may be gone, but its scientific bounty will keep us occupied for many years," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist, said in a statement. "We've only scratched the surface of what we can learn from the mountain of data it has sent back over its lifetime," she said.

"This is the final chapter of an amazing mission, but it's also a new beginning," Zurbuchen said.