A cosmological tourism park near the world's largest radio telescope in Guizhou, southwest China (Xinhua/Ou Dongqu)

By Ge Mengchao & Wang Caizhen

Albert Einstein says: "You do not really understand it unless you can explain it to your grandmother." Truly, it is not easy to make non-experts, like our grannies, understand science-related topics, but Bi Xiaotian enjoys meeting the Einsteinian challenge.

Bi, a PhD candidate in the Department of Chemical Engineering, Tsinghua University in Beijing, began to be known as a popular science writer in the past summer after his online article went viral by explaining why some drinks taste "terrible" in a scientific but amusing manner.

The article, illustrated with funny pictures and full of buzzwords, was written to respond to Internet users' spoofing selection of "Top Five Terrible Drinks." He compared the five soft beverages through chemical approaches.

The article on Weibo, a leading microblogging service in China, was retweeted 8,900 times with 17,000 comments.

A snapshot of Bi Xiaotian's Weibo webpage

Bi is one of the college students who have joined in the efforts of popularizing science in an era when Chinese people' s low science literacy becomes a concern in contrast to the present information overload.

According to statistics from the China Association for Science and Technology, only 6.2 percent of Chinese people held basic science literacy in 2015, lagging far behind the country's economic growth.

The low science literacy has protruded the dearth of effective science communication popularizing complex subjects like cosmology, quantum physics, evolution and anatomy to the public.

Bi's story related to science communication started two years ago when he, together with six classmates, accidentally became "defenders" of PX, a notorious chemical in the eyes of Chinese public.

PX, short for P-Xlyene, is a chemical compound widely used in clothing, manufacturing, pharmacy and the petroleum industry. Nevertheless, nearly all planned PX projects in Chinese cities over the past decade encountered boycotts and protests due to environmental concerns of the public. The same situation occurred in Maoming, Guangdong Province in 2014 again.

Bi says he understands the concerns of the protesters but he had something to say when he found that the chemical property of PX was intentionally changed from "low toxic" to "high toxic" by ulterior users at Baidu Baike, China's Wikipedia.

"I hate those people who manipulate the public by spreading rumors," Bi says. "Whether PX is low toxic or not is just a simple scientific issue."

Bi and other Tsinghua students launched a campaign to defend PX on Baidu, changing the property of the chemical into "low toxic" for 36 times in the week from March 30 to April 6, until the definition of the term was locked by Baidu's webmaster as "low toxic."

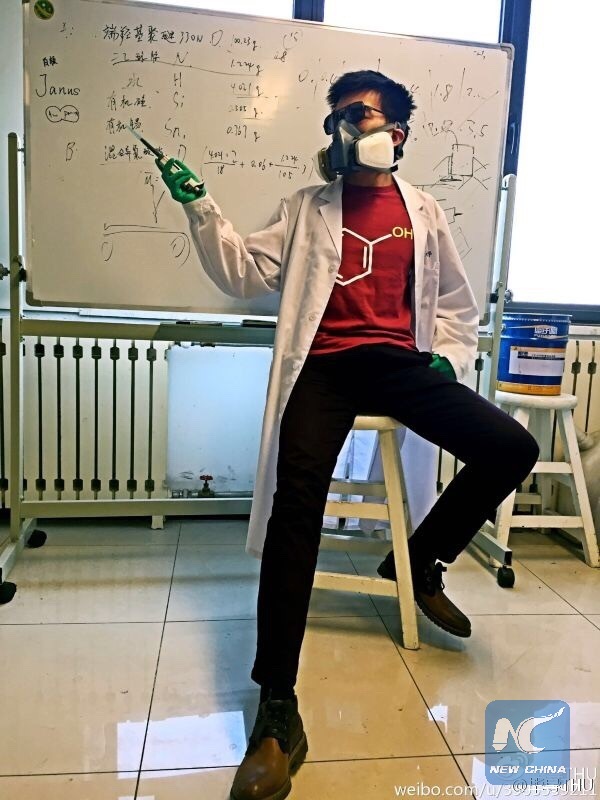

Bi Xiaotian, a chemical PhD candidate in Tsinghua University, poses for a picture in a lab. (Photo provided to New China)

NEW MEDIA SAVVIES

Like Bi, Sun Yafei, also a PhD candidate of Tsinghua's Chemistry Department, has had a similar experience.

Sun still remembered his first article concerning science communication. In that piece named Plasticizer's Chinese War, Sun introduced government attitudes and grounds towards plasticizer in Europe, the United States and Japan to the Chinese public.

Sun's article was published after a toxic plasticizer scandal in Taiwan triggered huge controversy and unrest among the international community, especially Asian countries in 2011, when it was exposed that the chemical product was wrongly added into food as an additive.

All of a sudden, food plasticizers were completely demonized. "I felt uneasy to see the non-professional comments on the web so I handed in my article to an editor of Squirrel Association," he says. Squirrel Association, short for Squirrel Association of Science Communicators, is a non-governmental organization that publishes books, organizes themed events and runs an Internet service.

Squirrel Association and Zhihu, China' s Quora, were not so popular and influential as they are today, but Sun has since become an opinion leader and an Internet celebrity. On Zhihu, Sun has gotten 31,000 likes, 9,800 thanks with 17,000 followers.

Nowadays, a growing number of Chinese netizens resort to Squirrel Association or Zhihu for expert opinions and scientific insights on social hot topics like environmental protection and safety of genetically-modified food due to lack of authority voices.

"These Internet platforms have allured loads of young intellectuals from universities and related industries," Sun says. "We share ideas and brainstorm together online."

On the one hand, the huge hunger for knowledge, with people as interested in and enthusiastic about science as they have ever been, happens to be a catalyst for promoting science communication.

It is far from enough, on the other hand. High academic authorities in China are generally reserved and reluctant to speak out their opinions and suggestions. As a result, college students like Bi and Sun are playing an increasingly significant role in defending scientific facts amid media hype and sensationalism as well as numerous misinterpretation prevailing among the public.

Various reasons are considered to have resulted in this phenomenon. Compared with poker-faced professors and experts who stay in labs surrounded by bizarre test tubes, students are easy-going and down to earth. As young adults and twitteratis, they understand their audiences better and are good at playing with trendy new media platforms. Except for Squirrel Group and Zhihu, these Internet savvies like to publish scientific articles on WeChat, China' s What's App, and Weibo, China's Twitter.

Another advantage for college students is that they are more likely to get in touch with leading scholars and researchers who can re-check their opinions. Moreover, driven by pure love of communicating and feeling of being worshiped, most of them tend to be less influenced or manipulated by vested interest behind science research.

A worker at a science exhibition in Hefei, east China's Anhui Province, explains to two pupils how solar power is generated on Sept. 22, 2016 (Xinhua/Zhang Duan)

ROLE OF PROFESSORS

Both Sun Yafei and Bi Xiaotian complain about their weaker influence on popularizing science. It is true that if a man is in a low position, his words are often of little effect.

"The dilemma of science communication in China is that students lacking experience are more eager to communicate with the public, while at the same time, professors with authority just say nothing," Sun says. "It is leading experts rather than I who should stand out and uphold the banner of communicating science and improving public' s intellect."

Last year, Sun's appeal was echoed by Zhou Gongdu, an 84-year-old professor at the School of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering of Peking University. By handwriting a letter, he accused an advertisement themed "We hate chemistry" on the China Central Television (CCTV) of misleading the public. Three days after that letter's release on the Internet, the advertisement was removed by the state broadcaster.

Conspicuously, scientists and professors in Chinese colleges have greater power and potential to communicate science but are less promoted and encouraged. "Professors do not like to communicate science as they think the public can not understand what they are talking about," says Jin Jianbin, professor in Tsinghua School of Journalism and Communication, "neither do they gain many rewards both monetarily and mentally."

However, Professor Rao Yi, Professor Xie Yu from Peking University and Professor Lu Bai from Tsinghua University have made a difference by establishing a company named Intellectual Media Ltd. last year. Their WeChat account The-Intellectual has attracted more than 320,000 followers.

The-Intellectual offers the public original articles about high-end science and technologies. In addition, it also participates in debates on hot social issues.

The-Intellectual is trying to create an atmosphere that makes lofty researchers and scholars feel more relaxed and pleasant by teaching them new media skills, supporting their hobbies or organizing seminars. Lu Bai, neuroscientist and professor in Tsinghua School of Medicine, says their aim is tantamount to influence the influential people who will lead others to love and communicate science.

Sun Yafei appreciates what the professors have done. "They are blazing a trail," he says.